|

The Kildonan Clearance |

| By Peter Lawrie, ©2017 A descendant of the Kildonan Clearance |

In 1807 Elizabeth Gordon, 19th Countess of Sutherland and wife of the Marquess of Stafford - a leviathan of wealth - wrote that "he is seized as much as I am with the rage of improvements, and we both turn our attention with the greatest of energy to turnips". As well as turning land over to sheep farming, Stafford planned to invest in a coal-pit, salt pans, brick and tile works and herring fisheries - none of which, poorly planned and executed, have survived. They also made hugely expensive additions to Dunrobin Castle for their rare visits to Sutherland. The image on the right includes further additions later in the 19th century. That year his agents began the evictions, and 90 families were forced to leave their crops in the ground and move their cattle, furniture and timbers to the land they were offered 20 miles away on the coast, forced to live in the open until they had built themselves shelters. This plan has been described Michael Fry in Clearances? What Clearances? as a "typical example... of social engineering which met neither the hopes of the benefactors nor the needs of the beneficiaries, but produced social disaster" |

|

|

The Countess, on seeing starving tenants on the estate, remarked in a letter to a friend in England, "Scotch people are of happier constitution and do not fatten like the larger breed of animals." The Staffords' first Commissioner, William Young, arrived in 1809, and soon engaged Patrick Sellar as his factor, who pressed enthusiastically ahead. In early 1813, Reed and Hall, farmers from the Borders, along with Clunes of Cracaig farm who had been invited by the Staffords to lease land in Sutherland for sheep, were confronted by a group of tenants in Kildonan who had some idea of their intentions. Later, Reed claimed that he had been attacked by a mob and had barely escaped with his life. |

|

In February 1813, the sheriff substitute, in session at Golspie Inn, had expected to deal with the fifteen men who had been identified as the ring-leaders of the 'mob'. Finding his temporary courtroom besieged by more than three hundred, he retreated to Dunrobin Castle. In his deposition, the sheriff officer named, among the fifteen, William MacLeod in Eldrable and Donald Polson in Torrish.

This was just the excuse which the factors, Sellar and Young had been praying for - . Staff from the estate were sworn in as special constables and a detachment of infantry sent from Fort George. This show of force caused the resistance to melt away. Within three months large areas of upper Kildonan had been entirely cleared and the people allocated tiny allotments of poor land on the cliff tops near Helmsdale. Or they chose exile in Canada, led by the Gunn tacksmen. Lady Stafford wrote in 1813 that she would like to visit her Sutherland estate: "but at present I am uneasy about a sort of mutiny that has broken out, in consequences of our new plans having made it necessary to transplant some of the inhabitants to the sea-coast from other parts of the estate". |

In June 1813 a shipload of 94 Kildonan people, sponsored by Lord Selkirk, left for Canada's Red River from Stromness in Orkney aboard the Prince of Wales. It was a hard passage, with some dying en-route, overwintering in the bitter cold on the shore of Hudson's Bay followed by an 800 mile journey before they found themselves embroiled in a conflict between the Hudson Bay Company and the North-West Company. They had to fight not only the harsh Canadian winter, but also hostile Indians and renegade Frenchmen. Their new settlement named 'Kildonan' is now a suburb of the city of Winnipeg. A further shipload of 84 left in July 1815 on the Hadlow. The grandson of James Sutherland, one of their number, was Angus Sutherland who became one of the 'crofter' MPs elected to Parliament in the anti-landlord agitation of the 1880s. A great-grandson of John Bannerman would become Canada's prime minister in the 1950s. In 1819 the last inhabitants were cleared from lower Kildonan by Francis Suther, the new estate factor. This time there was little dissent. The people had learned by bitter experience that neither government, nor law courts, nor their church, would speak a word or lift a hand in their defence. They went quietly into exile to the Lowland cities or joined their kinsmen across the Atlantic. Or they remained - to a bare existence on tiny patches of steep and barely cultivatable land in places such as West Helmsdale, as did my ancestors, Joseph MacLeod from Eldrable and Donald Polson from Torrish. Joseph MacLeod's grandson, also Joseph (and my great grandfather), would be a noted Land Leaguer of the 1880s and author of Highland Heroes of the Land Reform Movement. The recent monuments to the Exiles in Winnipeg and Helmsdale have been inspired and paid for by Dennis MacLeod, also a descendant of one of those who remained.. |

|

Donald MacLeod later wrote in Gloomy Memories in the Highlands of Scotland : "...the whole inhabitants of the Kildonan parish, with the exception of three families--nearly 2,000 souls--were utterly rooted and burned out". |

|

||||||||

|

|

Like the Strath of Kildonan,

Glen Loth has been settled for at least five thousand years. Carn Bran near the entrance to the glen is a tumbled iron-age broch. A few hundred metres further on the other side of the burn is another, better-preserved broch. There are standing stones dating from the Neolithic. RCAHMS lists in the Strath of Kildonan itself at least five brochs, eight souterrains, several stone circles and up to ten chambered cairns - evidence of a settled community over a very long time. |

|

| In Strathnaver, tenants in Rhiloisk were evicted in May 1814 and their houses burned by men under the supervision of Sellar to make way for a sheep farm leased by Sellar himself. With further leases taken in subsequent years, from 1819, Sellar controlled the whole of the west bank of the Naver for 25 miles, an area completely denuded of a previously substantial population apart from the shepherds he brought in. Accounts like that of Donald McLeod and General David Stewart of Garth brought widespread condemnation. Two old people evicted at Sellar's orders in 1814 had been too ill to be moved. He left them exposed to the chill northern air and they died. He was acquitted, by a jury of factors and landowners at the High Court sitting in Inverness, on a charge of manslaughter. However Lady Stafford wrote: "The more I hear and see of Sellar the more I am convinced that he is not to be trusted more than he is at present. He is so exceedingly greedy and harsh with the people, there are very heavy complaints against him from Strathnaver." In due course Sellar was dismissed from his post as factor, but he would make so much money from his lease of Strathnaver that in 1838 and 1844 he was able to purchase two estates in Morvern covering tens of thousands of acres. Here, he would evict another 250 small tenants. |

|

Donald McLeod, an eye-witness wrote in "Letter VII", Gloomy Memories in the Highlands of Scotland: "The consternation and confusion were extreme. Little or no time was given for the removal of persons or property; the people striving to remove the sick and the helpless before the fire should reach them; next, struggling to save the most valuable of their effects. The cries of the women and children, the roaring of the affrighted cattle, hunted at the same time by the yelling dogs of the shepherds amid the smoke and fire, altogether presented a scene that completely baffles description — it required to be seen to be believed. A dense cloud of smoke enveloped the whole country by day, and even extended far out to sea. At night an awfully grand but terrific scene presented itself — all the houses in an extensive district in flames at once. I myself ascended a height about eleven o'clock in the evening, and counted two hundred and fifty blazing houses, many of the owners of which I personally knew, but whose present condition — whether in or out of the flames — I could not tell. The conflagration lasted six days, till the whole of the dwellings were reduced to ashes or smoking ruins. " The limited clearance of part of Strathnaver in 1814 resulted in two deaths and Sellar's trial. In 1814, no provision had been put in place for the tenants of Rhiloisk to be settled on the North coast. In 1819 inadequate crofts on stony shores were on offer, but few were willing to take them. The scene as described by Donald MacLeod in Gloomy Memories did have some 'dramatic embellishment'. Especially as the houses destroyed covered the 28 mile length of Strathnaver, so it would be impossible for him to count all 'two hundred and fifty blazing houses'. However, around 250 families were evicted and their houses and farm buildings set ablaze in just one day in May 1819 with, as MacLeod states, very little time for removal of furniture and effects. The ultimate end of the process was the removal of the entire population without consultation and with derisory compensation to crofts which were far inferior to the farms which they left behind. |

|

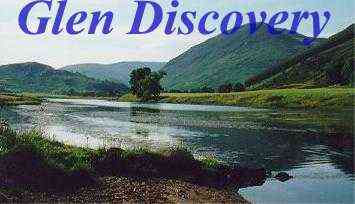

The parish of Kildonan was landlocked so the population reduction by 1819 was dramatic. During the late 1840s, boundaries were changed so the village of Helmsdale with the surrounding townships of Marril, Navidale, East and West Helmsdale were moved from Loth to Kildonan, thus complicating any analysis of the records. In addition most of the population joined the Free Church after 1845 so there are very few recorded after that as the Free Church birth and marriage records have been lost. The earliest decennial census in 1841 dates from well after the Clearances, so I have attempted a quantitative analysis of the Kildonan Clearances from the old parish record (OPR). Kildonan OPR started in 1791, while Loth only began in 1802. For my analysis I split the two parishes into pre-1820 and post-1820. This is not ideal as the Clearances began in 1807, but were particularly significant between 1813 and 1819. The first 'shepherds' appear in 1808. This aerial image, thanks to Highland Aerial Views, includes part of Old Helmsdale on the north side of the river and Marril to the south. Much of the green land in the distance is a modern golf course. A bright, sunlit modern colour photo does not properly convey the original brutality of the settlement. |

|

|

Each of the houses in the image originally had a strip of a very few acres judged to be just sufficient to keep a family alive. Lotters had to build their own houses at their own expense. Only favoured incomers in Helmsdale village proper or on the newly laid out large farms had buildings erected at the expense of the estate. The assumption was that the people would have to find work as labourers as well - provided any work was available for them. On the right is a plan originally part of the Sutherland estate maps dated 1813-1819, but taken from workshouses.org.uk showing some of the strips with the pauper houses known as 'The Barracks' intended to hold up to six families at the top. |

|

| Here, in support of my analysis from the OPR, is a summary of the census totals. The effect of the Clearance of inland Kildonan to coastal Loth between 1807 and 1819 is apparent in the drop of 1200 in the population of Kildonan and rise in Loth by almost 1000. This is quite apart from any natural increase to be expected in forty years. In the late 1840s the boundary change moved the totals in the opposite direction. The 1951 & 2011 figures demonstrate the futility of top-down development conceived by absentee landlords and executed by outsiders. |

Year Kildonan Loth ------ Total |

1801 1440 1374 ------ 2814 |

1841 237 2314 ------ 2451 |

1851 2285 640 ------ 2925 |

1891 1828 528 ------ 2356 |

1951 1338 252 ------ 1590 |

2011 725 139 ------ 864 |

|

Using the birth numbers alone clearly precludes the unmarried and couples whose last child was born prior to the start of the OPR, while giving undue weight to the more fecund couples. Identifying married couples with one or more recorded births rather than using the total number of births, still takes no account of childless and elderly couples, but is the best that can be done. There were 1232 births to 383 families (including 20 flagged as illegitimate) in Kildonan prior to 1820, and 259 births (5 illegitimate) to 99 families after 1820. In Loth, prior to 1820, 568 births to 230 families and afterwards 1560 births to 536 families (30 illegitimate - The illegitimacy rate was between 1.6 and 1.9%). The drop in population of Kildonan and increase in Loth is very apparent. However, there is also a generational shift as only a few families from pre-1820 Kildonan are still having children in post-1820 Loth. Examination of the rentals for Kildonan for 1808 to 1817 does not help as in general the renters are of the older generation and their possible children who may be having families after 1820 do not appear in the rentals. The dramatic decline in the Gunns and Bannermans is apparent. There were 54 Gunn families in Kildonan prior to 1820 but none thereafter while Gunns in Loth increased from 5 to 15. SImilarly, the Bannermans dropped from 27 to zero in Kildonan after 1820; rising from 12 to 23 in Loth. These two kindreds probably formed a large proportion of the emigrants to Canada. The MacKays and their Polson sept in Kildonan dropped from 59 to 15, rising from 31 to 79 in Loth. Sutherlands and Gordons in Kildonan dropped from 94 to 12, rising from 49 to 88 in Loth. This suggests that these four surnames formed much of the lower level of tenants in Kildonan and many of them probably cleared from their inland farms to the coast as a result of the Clearances. Similarly with the next five groups on North Highland surnames - MacBeath, MacLeod, Murray, Matheson and Grant - who numbered 77 families in Kildonan prior to 1820 and 8 thereafter, rising from 32 to 67 in Loth. Finally a further group of seven North Highland names - Fraser, Bruce, Ross, MacPherson, MacDonald, Munro and MacKenzie - dropped from 47 to 11 in Kildonan, rising from 42 to 89 in Loth. By contrast, many incomers to the parishes are apparent. In Kildonan, prior to 1820 there are just 25 (6.5% of 383) non-local names and 53 (53.5% of 99) after 1820. Ten of the twelve pre-1820 with occupation 'shepherd' are non-local. After 1820 there are 34 shepherds, five of which have local names. In Loth there were 61 (26.5% of 230) non-local names prior to 1820 and 175 (32.7% of 536) after 1820. Of these, 55 are single instances, such as Bell, Berry, Bethune, Boyne, Brock and Broomfield. The 18 top surnames among the families identified previously in Kildonan drop from 93.5% to 53.5% of the total. In Loth the drop is from 73.5% to 67.4%. While Loth has had a considerable influx of incomers, there is not a large drop in the 'locals' due to the resettlement of many of the 'Cleared'. An examination of the fathers' occupations is quite illuminating. In Kildonan 295 families prior to 1819 have the fathers' occupation recorded as 'tenant', only 8 such occur after 1820. A further 12 are 'IN' and 10 'residenter', these can be included in a total 380 families to the pre-clearance community of inland small tenant farmers. Very few occupations are recorded in Loth parish prior to 1828, After that there are 48 labelled 'labourer', 35 'lotters' and 10 masons. These 93 families are almost entirely to men with North Highland names located in the settlements of East and West Helmsdale, Marril, Navidale, Gartymore, Portgower and Culgower. Six of the 16 'farmservants' probably also belong to this group. Included in the post-1820 native married couples in Loth are 9 army pensioners, many of them survivors of the 93rd Sutherland Highlanders which had suffered very heavy casualties at the Battle of New Orleans in 1815. These men had been persuaded to join the regiment in 1799 by promises of security of tenure for their parents in their holdings. In 1813 Patrick Sellar brushed aside these promises as being of no significance. (Adam, Sutherland Estate Management) Fathers' occupations which only occur in Loth after 1828 include 15 shepherds (in addition to the 34 in Kildonan), 9 fishermen, 4 fishcurers, 39 coopers, 2 boatbuilders, 12 carpenters and cartwrights, 7 blacksmiths, and 9 merchants. Local craftsmen include 21 shoemakers, 6 tailors and 6 weavers. It may be suggested from the residence and names that some of these can also be numbered among the 'cleared', but many were incomers whose surnames do not occur prior to 1819. |

|

From the 1851 census, male heads of household, aged 40 or over therefore born before the Clearances were examined. In Loth, which by 1851 excluded Helmsdale and surrounding townships, 41 out of 63 were born in Loth and just 2 (both Sutherlands) were born in Kildonan, 15 of the remainder were from elsewhere in Sutherland, Ross and Caithness with 4 from other counties in Scotland and one from England. In Kildonan parish, which by now included Helmsdale as well as the strath, out of 239, 65 reported they were born in Loth (including some 'Kildonan-Helmsdale) while 93 were Kildonan - of these there were 9 Bannermans, 7 Gunns, 7 MacLeods, 18 Polsons and 8 Sutherlands. 57 of the remainder came from elsewhere in Sutherland, Ross or Caithness; 9 from Banff, 14 elsewhere in Scotland and 3 from England. |

|

In 1830 Lady Stafford made a rare visit to her Sutherland estate and found the tenants living in 'primitive hovels'. Unable to comprehend how people could live under such conditions, but speaking no Gaelic, she was not able to ascertain the condition of her tenants' lives and did nothing about it. When Lord Stafford, recently elevated as Duke of Sutherland, died in 1833, plans were made by those who had benefited most from his 'Improvements' for a monument to be erected on Ben Bhraggie in his honour. All householders resident on the estate were "requested" to contribute. Donald MacLeod wrote: "all who could raise a shilling gave it, and those who could not awaited in terror for the consequences of their default". |

|

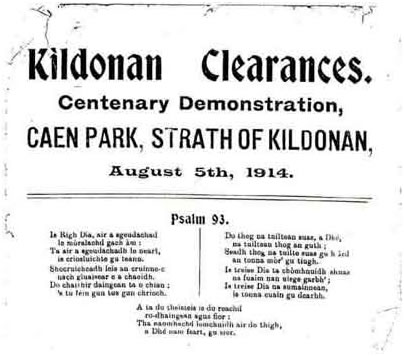

| The clearances psalm sheet.... Copy supplied by Kenny MacKenzie (red kenny the plumber) This sheet belonged to a George Munro of Navidale (Kenny's great grandfather) who happened to be the precentor that day. Shortly after the event the "toffs" came down with their hired "keepers" and forcibly removed all his papers photos etc. for burning. George had kept this order of service within a zipped bible and he challenged the intruder with the words "if you dare burn that bible you are really in trouble" this was enough to frighten him off , and so the bible was handed down to his son Angus who in turn gave it to Kenny in 1950....... |

|

In the 13th Century, the Seer Thomas of Erceldoune (Thomas the Rhymer or True Thomas) reportedly prophesied about the Highlands: "The teeth of the sheep shall lay the (useless) plough up on the shelf." Approximately 350 years later, Coinneach Odhar, the Brahan Seer,expanded on Thomas' vision: The day will come when the Big Sheep will put the plough up in the rafters... ...the Big Sheep will overrun the country till they meet the Northern Sea... ...(and) in the end, old men shall return from new lands... |

| The railway reached Helmsdale in 1870 and in the following years the line was completed to Wick and Thurso. While the new line gave a boost to the fishing industry, it threw the remaining craftsmen in the parish, the shoemakers and tailors, into poverty, as they were unable to compete with factory made goods from the South. Ultimately it would sound the death knell of large scale sheep farming which was already in decline due to exhaustion of the arable land created so laboriously over centuries by the victims of the Clearances. From now on, the railway would provide easy access for the wealthy to enjoy their summer breaks - shooting deer or grouse and fishing for salmon. Fancy lodges would be built in the Strath and increasingly, the shepherds would be cleared in their turn and the conversion of thriving rural communities to a man-made desert completed. |

A feature on the 'World Railways' website describes the inland route of the line, avoiding the steep Ord of Caithness, on its way to Wick. The seashore is followed closely to Helmsdale where the route heads inland. This is spectacular country as the line threads its way up the Strath of Kildonan with signs of habitation decreasing as the coast is left further behind. Wild moors with snow fences along the line suggest that winters might be harsh. Small stations are passed without stopping - Kildonan and Kinbrace were both listed in the timetable as request stops. There was not even a sheep in sight! |

Iain Fraser Grigor, provides an excellent synopsis of the fate of the Highland people since 1745 in Highland Resistance (Mainstream, 2000) - "After 1745 the Highlands of Scotland became subject to first a military and then a commercial and finally a recreational colonial occupation. The chief features of this would become clearance and emigration; the exploitation of natural resources through large scale sheep-farming and deer-afforestation; the exploitation of population resources through military recruitment; the smashing asunder of the traditional society and its established class relations; the divorce by force of the common people from the occupancy of a land they looked upon as their own; and the invention of a tradition identified today as the cult of Balmorality. The process was crude but it represented for the government a very firm grasp of the essentials." The Gaelic poet John MacCodrum wrote 'Look around you and see the nobility without pity for poor folk, without kindness to friends; they are of the opinion that you do not belong to the soil, and though they have left you destitute they cannot see it as a loss'. Andrew G Newby states in Land and the “Crofter Question” in nineteenth-century Scotland,- "The Improvers could not foresee, even less understand, the reluctance of the Highland population to move away from traditional agriculture, and the early years of the nineteenth century witnessed a huge push towards rationalization of some Highland estates. Events on the vast lands of the Countess of Sutherland, between 1807 and 1821, have come to symbolise the human consequences of Clearance. Her marriage to one of England’s wealthiest landlords, the Marquess of Stafford in 1785 ensured that there would be the resources to pay for estate reorganisation. This was given further impetus by the arrival of Morayshire farmers William Young and Patrick Sellar in 1809. Both were zealous Improvers, but the speed with which they proceeded in attempting to establish sheep farms in Kildonan led to riots in 1813. The forced evictions and burning of house roofs and frames — along with the trial of Sellar for the culpable homicide of an elderly tenant — became an important symbol of the oppression of landlords and their managers in the Highlands. The trial ensured increased public awareness of the Clearances in Great Britain, and under the management of James Loch the estate became more sensitive to public opinion. Nevertheless, rationalization and eviction continued into the 1820s." While the practicalities of Highland lifestyle may well have been less than idyllic, there are many accounts of Highland life by independent observers such as James Boswell, Samuel Johnson, Thomas Pennant and others, which showed that there was much in Highland life and culture which was to be admired. The people, far from being lazy, were hospitable and industrious. Their homes while simple, were practical, and well suited to their environment. Highland culture, although largely oral (and therefore greatly undervalued by outsiders) was rich in song, history and legend. Landlords, and more particularly, their agents, repeatedly blackened the Highland character. They claimed that the Highlanders were lazy, idle, drunken, ignorant and dirty. This discourse was identical to that used by imperial powers to denigrate their subject peoples, and portray colonised people around the world as less than human and undeserving of respect. These are the tactics of bullies, dictators and oppressors of humanity everywhere. Their victims have to be dehumanised so that crimes against them will not be seen as crimes but as necessary actions. |

|

On 23 July 2007, the Scottish First Minister Alex Salmond unveiled a 3-metre high bronze Exiles monument, by Gerald Laing, in Helmsdale, commemorating the people who were cleared from the area and left their homeland to begin new lives overseas. The statue, which depicts a family leaving their home, stands at the mouth of the Strath of Kildonan and was funded by Dennis MacLeod, a Helmsdale born mining millionaire who also attended the ceremony. An identical 3-metre high bronze Exiles monument (shown above) has also been set up on the banks of the Red River in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada. |

| For a chronology of the Highland Clearances, see The Highland Clearances. |